GameStop is the largest video game retailer worldwide.[1] At its 4,816 stores, customers can purchase new or used video games, gaming consoles and accessories or trade in their old items for cash or credit. It’s a simple business, but one that, like many other businesses, is being supplanted by online purchases in our increasingly digital world. It had been a sad story for shareholders leading up to 2020. On April 2nd, 2020, the stock closed at its intraday low of $2.85 a share—its lowest price since February of 2003 and well below its IPO price in 2002. Fast forward nine months to January 12th, 2021, the stock had quietly risen 700% to $19.95 a share. The next day, January 13th, 2021, the “meme” stock was born. The stock closed at $31.40 a share, a 54% intraday rise from its $20.42 opening price, and traded as high as $38.65. Two weeks later, the stock would change hands at $380 a share—a 13,000% increase from its pre-pandemic low.[2]

The “meme”[3] stocks are one of the most unique happenstances in the history of modern markets. Newly minted retail traders, drunk on gains from pandemic story stocks and looking for a way to entertain themselves while stuck at home, lit the fuse in a handful of left-for-dead retail stocks and the rest is history. At the center of it all was the online retail brokerage firm Robinhood. “Democratizing finance for all” by streamlining stock and option trades placed on your phone with a handful of confetti for good measure. As a public company, Robinhood releases a plethora of interesting data on its unique cohort of users. The most recent quarter’s earnings report told a story of waning enthusiasm, prompting the question—is this the end of the “meme” investors?

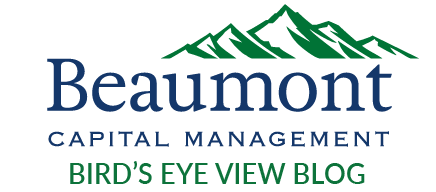

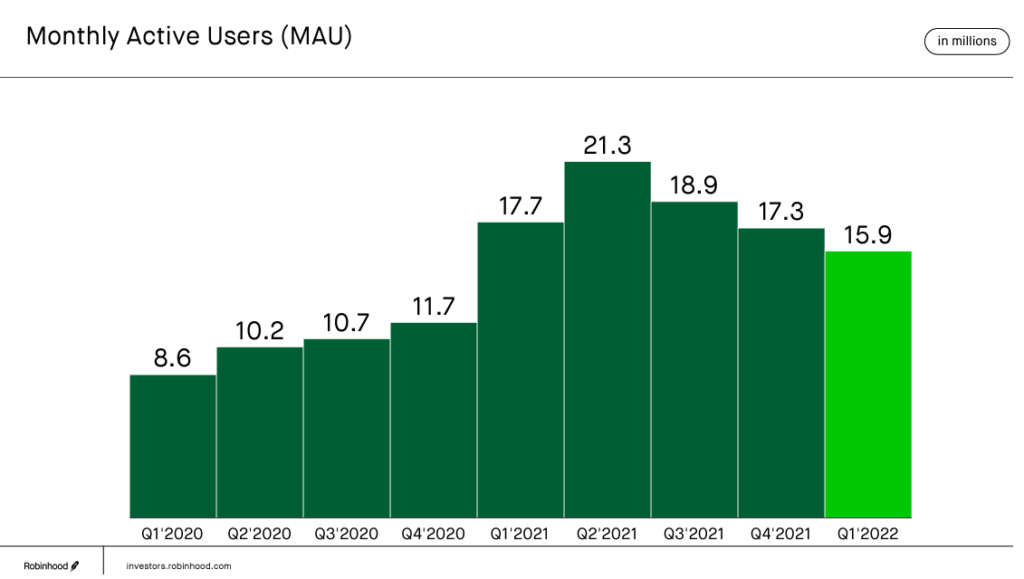

At the beginning of the pandemic in the first quarter of 2020, Robinhood had 7.2 million “net cumulative funded accounts” (a fancy way of saying accounts in good standing). The number of accounts tripled, to 22.5 million by the second quarter of 2021. During the “meme” stock craze, liberally defined as the first and second quarters of 2021, Robinhood added 10 million new accounts. Since then, growth in new accounts has come to a halt and enthusiasm has faded. Monthly active users[4] have fallen by 25% and, more concerning for investors, average revenue per user has plummeted.

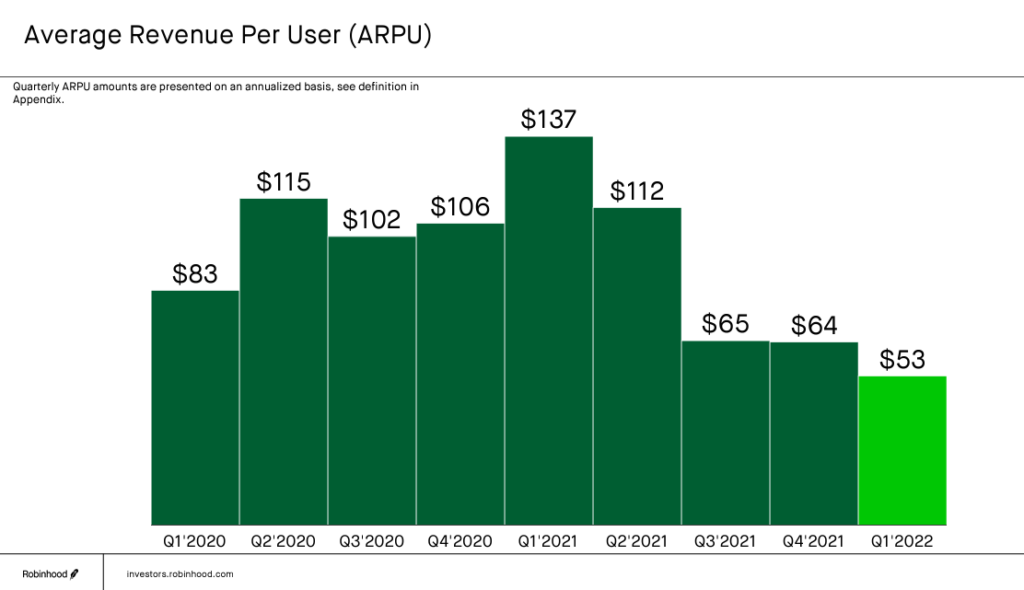

While Robinhood’s business model is relatively straightforward, the source of its revenues may surprise you. In the average quarter, about 75% of revenues are transaction-based, 17% from net interest, and 8% other. The common perception is that Robinhood is a stock trading app, but its business is options (with a brief foray into Doge coin in the second quarter of 2021). Option transaction volume has accounted for 42% of revenue on average.

Options may be great business for an online brokerage, but they’re akin to lighting money on fire for retail investors. A recent study[5], “Retail Trading in Options and the Rise of the Big Three Wholesales,” estimated that retail investors lost $1.14 billion trading options from November 2019 to June 2021 while paying $4.13 billion in transaction fees.[6] Notably, this study concluded before the recent declines in many of the stocks most loved by retail investors.

Robinhood’s most recent quarterly earnings release does make one thing clear—the type of investors who are commonly accused of igniting the “meme” stock craze are losing interest. How could they not? The “meme” stocks were (hopefully) an aberration in market history. Despite periodic rallies and surprising resilience, it’s been over a year and the stocks haven’t regained their former glory. Buying out of the money call options made a few people rich for a short period of time, but in most others, those engaged in this strategy are destined to lose. Robinhood’s user base tells a similar story—buying expensive lottery tickets loses its luster eventually. There will be other periods of speculation in the future, but it appears that the era of the “meme” stock investors is ending, if it hasn’t already.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GameStop

[2] Koyfin

[3] “Meme” definition: an amusing or interesting item (such as a captioned picture or video) or genre of items that is spread widely online especially through social media.

[4] Defined in the earnings release as “a unique user who makes a debit card transaction, or who transitions between two different screens on a mobile device or loads a page in a web browser while logged into their account, at any point during the relevant month”

[5] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4065019

[6] Quoting from the abstract, “We find that retail traders prefer cheaper, weekly options, the average quoted bid-ask spread for which is a whopping 12.3%, and lose money on aggregate.”