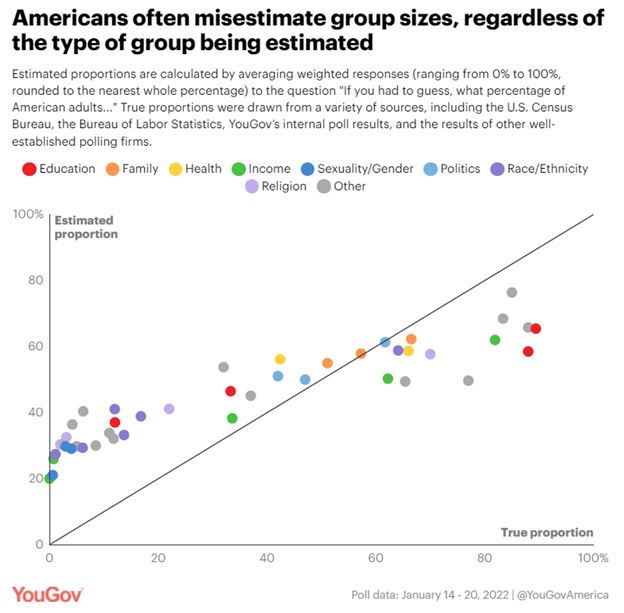

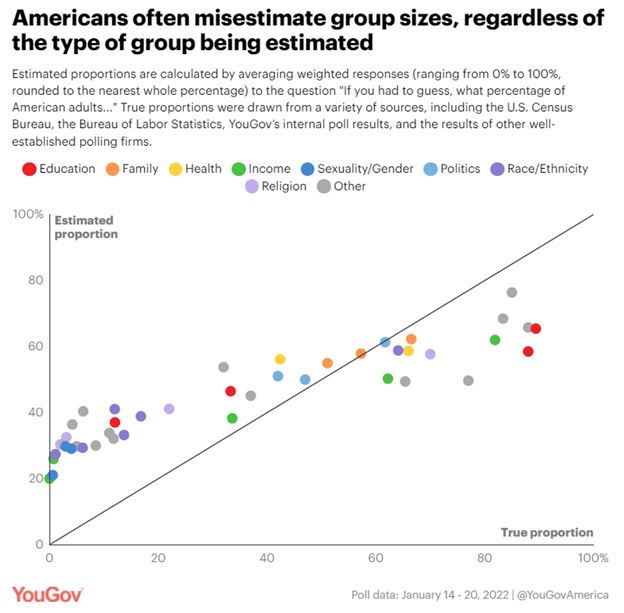

Behavioral finance plays a big role in the way that we think about investing. The idea that investors have consistent biases, many of which lead to suboptimal investment outcomes, is commonly accepted by investment professionals but may be less intuitive to those who are not professional investors. Therefore, we sometimes find it helpful to use examples of biases from different domains to help illustrate a similar idea. Along these lines, this chart from a YouGov survey from January 2022 on the representative proportion of different groups in America stuck out to us. The survey covered a wide array of different groups, everything from owning a car to being left-handed, and compared the survey results to rigorous estimates of true proportions. The results are clear, respondents overestimated the prevalence of smaller groups and underestimated the prevalence of larger groups.

To me this illustrates a foundational concept—people are bad at estimating the prevalence of events. Using the two prior examples, survey respondents answered that 68% of Americans own a car and 34% are left-handed—the true proportions are 88% and 11%.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that under uncertainty, people tend to take an otherwise rather smart approach. If you had no knowledge of the prevalence of a trait in a given population, your initial guess may be 50%. As you incorporate knowledge of the population, you move away from the base case. As the survey results indicate, respondents know that fewer than 50% of people are left-handed and more than 50% own cars so they move their estimate away from 50% in the correct direction but with the incorrect magnitude. As we stated, this is a smart approach! But it leads to the wrong answer despite being directionally correct.

Another possible explanation is that people more generally tend to overestimate the prevalence of rare events and underestimate the prevalence of common ones. Rare events stick in your memory, you may remember that your friend is left-handed or that they don’t have a car but don’t think about those traits as much when the opposite is true. Again, this isn’t necessarily bad, in fact there may be reasons why we evolved this way, but it leads to the wrong answers.

We believe that investors bring these same biases that lead to directionally correct but precisely incorrect answers with them as they interact in investment markets, causing subtle inefficiencies that a sophisticated quantitative model can take advantage of. Unfortunately, in financial markets, the opportunities are not quite as large as a 20% deviation between the market estimate and the true probability of an event occurring, but we believe these deviations do exist. Instead of relying on our own biased judgement, we use a quantitative investment system driven by machine learning to detect and exploit such inefficiencies in a systematic manner.