Written by BCM Investment Team

Investment Losses in Terms of Percentage, Time and Dollars

April 20, 2019 | ECONOMICS & INVESTING

What is risk? How do you measure it? In investing, risk can mean a lot of things to a lot of people. Industry professionals would typically answer volatility (VIX), standard deviation, Sharpe ratio, beta, and the list goes on. While those are technically correct, as money managers, we have to think like investors. What does “risk” mean to them?

BCM’s investment team has a background in financial advisory. What they found after years of working with their clients is that those aforementioned measures of risk have little meaning to clients or end investors. Investors have one concern: how much money do I stand to lose? This is drawdown.

Underlying all BCM strategies is the notion that ultimately, the real risk to a portfolio is the risk of a large loss, or as one of our analysts recently put it, “the risk of ruin” or “risk of permanent impairment.”

“Buy and hold” enthusiasts that are reading this right now are likely shaking their heads but stay with us. In theory, we agree with you and Warren Buffett—buy and hold has been the best investment strategy over the long term. However, this notion comes with two huge assumptions:

- That the average investor will actually be able to stomach the large losses throughout the entire drawdown and recovery of each market cycle.

- That even if they could handle this emotionally, they have enough time to recover before they need their money.

Let’s be honest with ourselves, most investors don’t meet the criteria of these two assumptions. That is why large losses present the risk of “permanent impairment”. We will illustrate this with three key elements: investment returns, time and dollars.

Losses in Terms of Investment Returns

Many people don’t appreciate the concept that when a portfolio sustains a large loss, an outsized gain is required to break even. Here is a chart to explain this concept:

If your portfolio loses 20%, it takes a gain of 25% to get back to even. Looking back to the ~55% loss that the S&P 500 experienced in the 2007-2009 drawdown, this would require a 123% gain just to get back to even. Many types of investments, and many investors, lost even more.

Now let’s put this into terms of time.

Losses in Terms of Time

While stating this concept in percentage terms is compelling, when you look at it in terms of time, it’s a little more eye opening.

In the spirit of keeping this as realistic as possible, we are going to assume an average annual return of 17%. We selected 17% because that is the average annual return of the S&P 500 during the recoveries of the last five bear markets (or in other words, the last five bull markets) rounded down to the nearest whole number. A 20% loss, which is about the drawdown the S&P 500 just faced in December, would take 17 months to recover from and a 50%+ loss would require 53+ months to recover. Again, these figures below assume that the investor stayed invested through the whole drawdown and recovery.

Drawdown |

Months to Recover |

| -10% | 8 |

| -20% | 17 |

| -30% | 27 |

| -40% | 39 |

| -50% | 53 |

If you combine the amount of time during which your portfolio would have started losing money with the time of the recovery, you are talking about years of no growth.

Let’s Talk About This Using Dollars

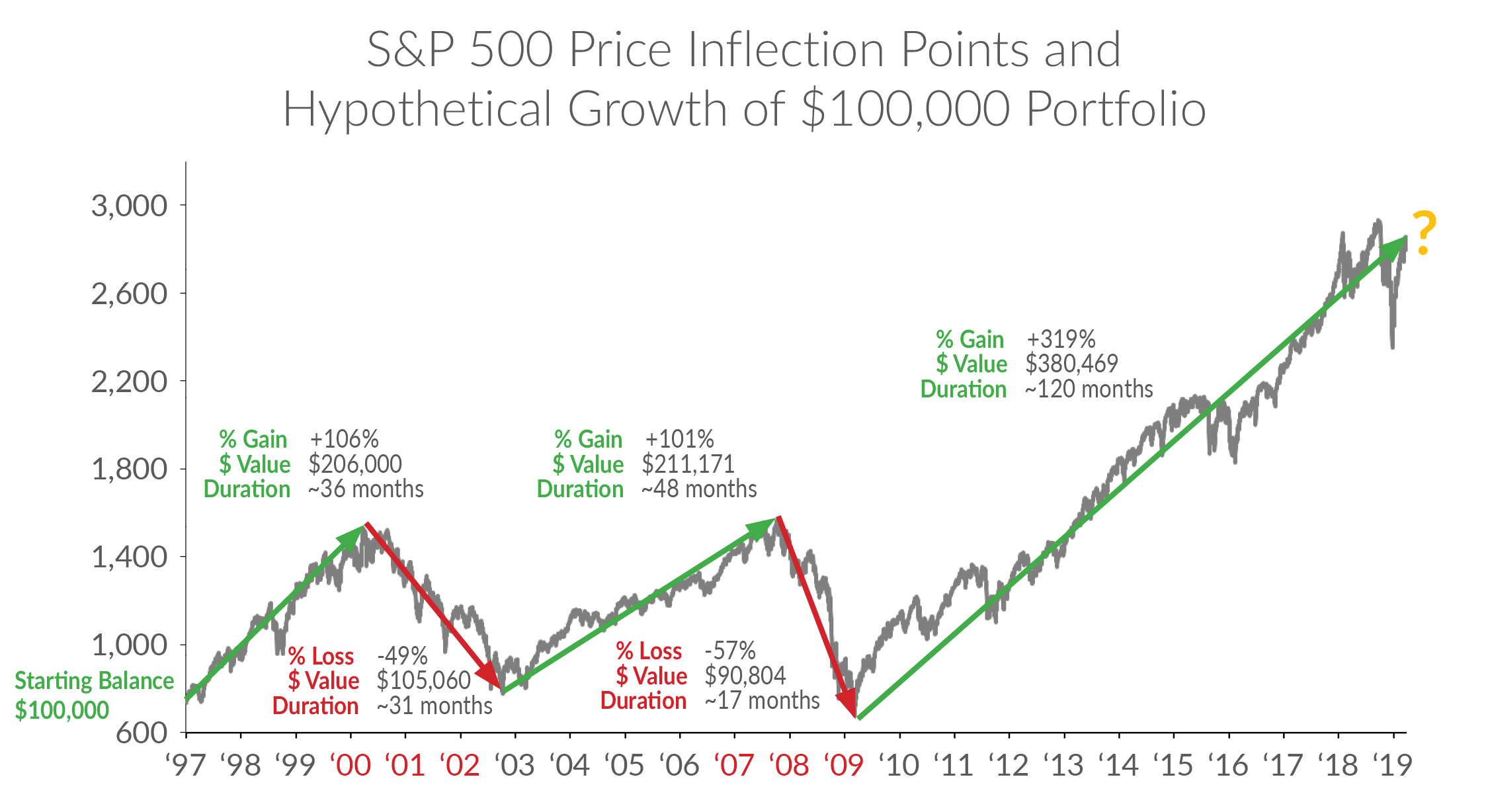

Follow the chart below: let’s say you have an account with $100,000 invested in an S&P 500 indexed fund (gross of fees) at the start of 1997, a few years prior to the “dotcom bubble”. By the end of the dotcom bubble, you have just $5,060 of growth. Then, by the peak of the bull market of 2002-2007, your portfolio would have grown to just $211,171. That’s just $5,171 more than the peak of the previous bull market. As you continue throughout the chart, you can see the effect of bear markets on a portfolio. I know this sounds repetitive, but once again, these figures still assume the investor didn’t capitulate at some point during the bear market. Currently, we are in a near-decade long bull market and no one knows where the market will go from here.

Now Let’s Apply This to a Typical Investor Scenario

Investors in or near retirement are the most sensitive to a bear market. While other financial goals can be ruined by large losses, retirement is a bit more “unavoidable”. We wanted to apply the concepts explained above to fully illustrate the effects large losses can have on an investor’s portfolio.

Let’s say a retiree starts with the following:

- Portfolio Allocation: 50% Equity/50% Bonds (assume indexed funds gross of fees)

- Starting Dollar Amount: $100,000 (just to keep the math easy)

- Annual Withdrawal Rate: $5,000 or 5%

Then there’s a bear market like 2007-2009:

- Assuming 50% Equity/50% Bond portfolio lost ~25% or about $25,000

- Remaining Principal = $75,000

- Annual withdraw is still $5,000

- This drops you down to $70,000 at the start of Year 1 of the recovery.

The recovery:

Assuming an average 10% return on the 50% Equity/50% Bond portfolio in Year 1 of the recovery (using the previously stated 17% average annual return for equities, and 3% for bonds in line with the current bond cycle).

Remaining Principal After Bear Market and Annual Withdrawal |

$70,000 |

Recovering of 10% in Year 1 |

$7,000 |

Ending Balance at End of Year 1 |

$77,000 |

Annual Withdrawal in Start of Year 2 |

$5,000 (now 6.5% of portfolio) |

Starting Balance in Year 2 of Recovery |

$72,000 |

After a year of “recovery”, your portfolio is lower than it was at the end of the bear market.

Risk of Permanent Impairment

This is a very simplistic example meant to illustrate how detrimental large losses can be and how they can prevent investors from meeting their financial needs. As a portfolio suffers significant losses, especially in or near retirement, the need to live off the portfolio further erodes subsequent gains. Even for investors not in retirement, emotional buying and selling will typically have a similar effect on the portfolio’s ability to recover. This is what we mean by “the risk of permanent impairment”.

We believe that every portfolio should have some degree of defense on at least a portion of the assets. Not only can this help reduce volatility and drawdown, but when investors know there is some level of protection, it may help prevent them from reacting emotionally during tumultuous markets. If you need help incorporating defensive strategies into your portfolios, we’re here to help.

Sources and Disclosures:

Copyright © 2019 Beaumont Financial Partners, LLC DBA Beaumont Capital Management (BCM). All rights reserved.

As with all investments, there are associated inherent risks including loss of principal. An investment cannot be made directly in an index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This material is for informational purposes only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or financial instrument, nor should it be construed as financial or investment advice. The information presented in this report is based on data obtained from third party sources. Although it is believed to be accurate, no representation or warranty is made as to its accuracy or completeness. The views and opinions expressed throughout this presentation are those of the author as of 4/18/19. The opinions or outlooks may change over time with changing market conditions or other relevant variables.

“S&P 500®” is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s, Inc., a division of S&P Global Inc.

Beaumont Financial Partners, LLC-DBA Beaumont Capital Management,

250 1st Avenue, Suite 101, Needham, MA 02494 (844-401-7699)

Popular Posts

- 4Q24 Commentary: Priced for Perfection – S&P 500 Increasingly Dependent on the AI trade

- Factor Investing: Smart Beta Pursuing Alpha

- Artificial Intelligence Doesn’t Appear Ready to Take Over the World Yet

- Personal Spending Recovers, Comparing 2020 to Past Recessions, and a Looming Threat to DB Plans

- ‘De-Worsifying’ Equities, U.S. Dividends Fail to Measure Up, and Are Junk Bond ETFs Turning to Junk?