Written by David M. Haviland

The Anatomy of a Bear Market

June 2, 2020 | ECONOMICS & INVESTING

What does a typical bear market look like? How long do they last? When are the majority of the losses incurred?

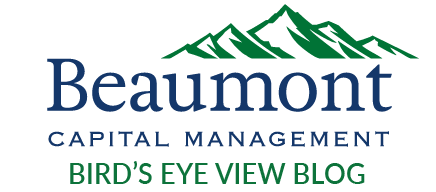

Most investors believe that the losses occur fairly evenly throughout a bear. Based on the past, with one and now possibly two notable exceptions, nothing could be further from the truth. In another piece we wrote about bear markets, Tactical to Practical: Understanding the Importance of Market Declines, we wrote about the types, frequency, severity and duration of market declines. Here are the results:

Source: Bloomberg, Beaumont Capital Management (BCM). Data as of 12/31/19.

Now let’s dig into what we really want to talk about: the anatomy of past bear markets.

First, Black Monday in October 1987 was the exception (until this year…we will get to that). The vast majority of the losses occurred in one day; in fact, the 22.6% loss was the largest one-day percentage drop in the history of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. In our opinion, this was truly the first “flash crash” as the computers of the day were selling ahead of their human counterparts. There were no governors or circuit breaker rules limiting the computer trading at the time, which exacerbated the fall. Regardless of the cause, the 1987 bear market was unlike any other in the post-WWII era due to its speed—until the 2020 event, still not known if over, halved the record-fast decline time.

Aside from 1987 and the current bear market, as the chart above illustrates, most bear markets take time. It takes a year or two to lose such a large percentage of your portfolio. Yet, within this timeframe, the losses are not evenly distributed. The chart below breaks down the average bear market for the S&P 500® Index. What is striking is that most of the losses occur during the beginning and the end of the bear market, and that the losses occur faster during those periods.

Source: Bloomberg, Beaumont Capital Management (BCM). The chart shows the distribution of losses throughout the progression of the average S&P 500 bear market (with dividends reinvested) since the end of WWII, excluding the 1987 bear market.

Every bear market starts as an ordinary pullback, grows into a correction and then continues into a bear. Ordinary pullbacks tend to be sharp and quick, so it makes sense that the beginning of all bears share this trait. Of all bear markets since WWII (except 1987 and the current bear market), the first quarter of the bear market (in terms of duration) declines ~9% on average—the upper range of the ordinary pullback. Historically, on average, the first quarter of a bear will incur about 26% of the total bear market drawdown as seen in the chart above.

The next phase, or the next half of the bear including the second and third quarters, is more of a complacency period. Combined, the average losses in this phase are 28% of the total loss. The bear takes its time. It pulls you in. There are cyclical recovery rallies sprinkled in giving hope. The shallower downward slope does not compel action but by the end of the third quarter, the bear has essentially doubled your loss. Complacency turns to denial. Lots of investors stop opening their statements. And then it happens.

Almost half of the bear market losses, 46% on average, occur during the final panic and capitulation stages of the bear market. During this final quarter, the declines tend to accelerate, and the markets start to cascade down. Even the most resolute investors have doubts. People freeze with fear not knowing what to do, and then most reach their breaking point. Emotions begin to take control and the fear that future goals—such as education and retirement—may become unachievable grows unbearable (pun intended). Most investors capitulate and sell at or near the bottom. This last phenomenon was even true during 1987.

What is the lesson? Investment math teaches us to keep our losses small. The larger a loss becomes, the greater the gain the remaining assets in the portfolio need just to get back to even.

Source: Bloomberg. Loss shown for S&P 500 Index is based on daily pricing and includes dividends reinvested from peak to trough for the most recent Bear market (time period 10/9/2007-3/9/2009).

Another lesson is to acknowledge the shape of a bear and the length of time it takes to unfold. As we mentioned above, the first 10% or so is almost impossible to avoid as it is quick and most often just an ordinary pullback. But as losses extend, it is time to re-assess. Acting before your losses leave the teens is quite easy to recover from as the loss diagram on the previous page illustrates. Keep your losses smaller and don’t be afraid sell into a rally.

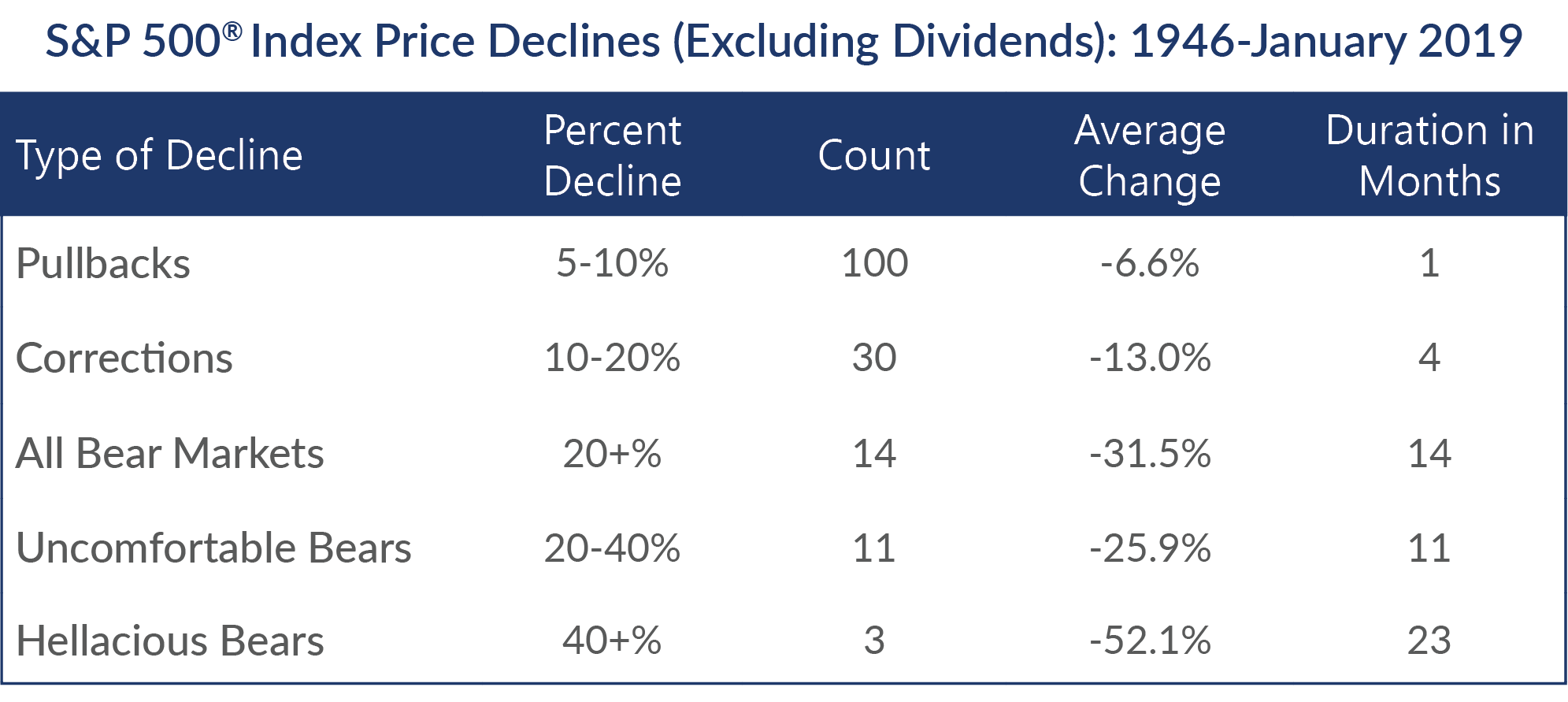

Truthfully, no one typically knows when a bear market is starting until it is too late. To further illustrate this, let’s look at how the last few bear markets unfolded:

Source: Bloomberg, Beaumont Capital Management (BCM). 2000-2002 Bear market dates between 3/24/2000-10/9/2002. 2007-2009 Bear market dates between 10/9/2007 and 3/9/2009. Current bear market dates between 2/19/2020 and 4/9/2020.

Of course, every bear market is slightly different but looking at these bear markets, the first 10% drawdowns look mighty similar. And the circled acceleration during the capitulation selling is quite obvious. You can also clearly see several rallies throughout. Even the lightning-fast 2020 bear had ~10% recovery rallies…they just occurred in one or two days.

As we discussed in our 1Q20 quarterly commentary, the 2020 bear market has been unprecedented in its speed, severity and recovery. However, it is still unknown if the bear is over or if there is going to be another leg down.

To many investors, the first sign they’re in a bear market is having lost a devastating amount of money. But if no one knows they’re in a bear market, how will they guard against loss? This is where BCM strategies can help. We provide growth systems designed to prevent large, devastating losses. Our systems ebb and flow as the market action unfolds, but without fear and greed clouding decisions. To BCM, it is simple: Follow a rules-based system that is designed to remove emotion from the investment decision making process.

Sources and Disclosures:

Copyright © 2020 Beaumont Capital Management (BCM). All rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed throughout this paper are those of the author as of June 2020. The opinions and outlooks may change over time with changing market conditions or other relevant variables.

The information presented in this report is based on data obtained from third party sources. Although it is believed to be accurate, no representation or warranty is made as to its accuracy or completeness.

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not in any sense constitute a solicitation or offer for the purchase or sale of securities nor should it be construed as investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. An investment cannot be made directly in an index.

“S&P 500®” is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s, Inc., a division of S&P Global Inc.

As with all investments, there are associated inherent risks including loss of principal. Stock markets, especially foreign markets, are volatile and can decline significantly in response to adverse issuer, political, regulatory, market, or economic developments. Sector investments concentrate in a particular industry, and the investments’ performance could depend heavily on the performance of that industry and be more volatile than the performance of less concentrated investment options. Foreign securities are subject to interest rate, currency exchange rate, economic, and political risks, all of which are magnified in emerging markets. The risks are particularly significant for ETFs that focus on a single country or region. The ETF may have additional volatility because it may be comprised significantly of assets in securities of a small number of individual issuers.

The portfolio manager maintains full discretion over the portfolio.

Popular Posts

- 4Q24 Commentary: Priced for Perfection – S&P 500 Increasingly Dependent on the AI trade

- Factor Investing: Smart Beta Pursuing Alpha

- Artificial Intelligence Doesn’t Appear Ready to Take Over the World Yet

- Personal Spending Recovers, Comparing 2020 to Past Recessions, and a Looming Threat to DB Plans

- Tactical to Practical: Understanding the Importance of Types of Market Declines